At 1.55pm on Sunday 21 July 2019 Shane Lowry looked worried, his worst fears were becoming reality – sooner and more emphatically than he feared.

Lowry was the leader in the 2019 Open Championship at Royal Portrush, carrying a four-shot cushion into the final round. Four shots is a relatively comfortable margin, but in golf, disaster lurks.

On the first hole, it looked to be unravelling. Two poor shots left Lowry in the bunker, and after chopping out and making his first putt he faced a second for bogey, his playing partner Tommy Fleetwood was putting for birdie. If Fleetwood holed his putt and Lowry missed, the four-shot lead would become one.

History Repeating Itself?

In 2016 Lowry squandered a four-shot lead in the US Open final round, setting in motion the unravelling of his career. His world ranking plummeted, and he missed the cut in four British Open Championships.

The night before the final round at Royal Portrush the press had its story: can Lowry hang on this time? He was obliged to face his demons in front of the world. When pressed by journalists on whether his past failures preyed on his mind, he responded: “I feel like I’m a different person now. I think that will help me tomorrow.”

Who knows whether he believed this, but the reality would soon become clear in front of millions of people – there was nowhere to hide.

After three days of mentally and physically tiring golf, countless questions about his previous failures, and his lifelong dream within his grasp, Lowy was required to go home and spend the night and following morning waiting for his final round.

Redemption

Back to the first hole: Lowry held his nerve and made his putt, Fleetwood missed and the lead was at three shots. Lowry never looked in trouble again – battling horrendous conditions he picked his way through the treacherous course to win by six shots.

Lowry was the Open Champion. He had succeeded under extreme pressure, somehow emerging from his previous failures stronger and better.

How could a man who had been through so much in his career, who was left crying in the car park after missing the halfway cut in the 2018 British Open 12 months previously, bounce back to win golf’s most prestigious title?

The Science of Resilience

The story of Lowry brings to mind a book by Martin E.P. Seligman, a Professor of Psychology, called Flourish, A Visionary New Understanding of Happiness and Well-Being. You can read a short article on the book in The Harvard Business Review article ‘Building Resilience’.

Seligman talks about two MBA graduates (actually fictional composites from a body of interviewees) called Douglas and Walter. After being laid off from their jobs both take different paths: Douglas is downbeat for a while before working hard to find his next role, whereas Walter slips into a malaise and moves back in with his parents.

The book asks the question: how can we help people behave more like Douglas and less like Walter? Seligman is part of a group using thirty years of research to figure out the best way to teach resilience.

A key example cited in the book by Seligman is a US Army-commissioned programme designed at making soldiers more psychologically resilient – the Comprehensive Soldier Fitness (CSF) Initiative.

This three-part programme is designed to help soldiers deal with the rigours of military life, and specifically how to bounce back from adverse situations. It covers a psychological evaluation, online course and face-to-face training programme. The aim is to help soldiers develop positive emotion, engagement, relationships and accomplishment – key components for resilience and growth.

There are many interesting elements to the training, and I want to focus on one in particular.

Soldiers are taught to recognise when feelings of sadness and anger become disproportionate to reality by looking at best, worst, and likely outcomes to adverse events. By quantifying the possible outcomes, participants are able to see that really bad outcomes are unlikely and can refrain from negative thinking – they are more likely to be circumspect.

Perhaps Shane Lowry used similar techniques? We will never know what was going through his head, but somehow he remained positive on that final round and stopped any negative emotions distracting him from his objective.

Stay Positive in Sales

My message here to sales professionals is to remain positive. The military training programme teaches many skills, and the concept of seeing every negative thought through a prism of varying outcomes can be effective.

I see sales professionals trapped in negative thinking

“I did a poor job pitching.”

“That client is going to a competitor.”

“I’m not going to hit my quota.”

Let’s consider a salesperson who doesn’t close a deal; they might be constructing a negative narrative in their mind – they weren’t good enough… they didn’t close hard enough… they didn’t build good enough rapport.

Some of these points may be true, but if the salesperson is competent, the reality is that the sale probably didn’t close because of timing, internal politics, emerging crises or a myriad other reasons outside of their control.

In sales, leaders can be guilty of pushing teams too hard and fostering negativity, paranoia and fear. Leaders should spend more time thinking about creating a positive mindset by avoiding thinking about the worst-case scenario.

It wasn’t fear that saw Shane Lowry come through the biggest test of his professional life, it was somehow tapping into a positive mindset – something we must think more about as sales leaders.

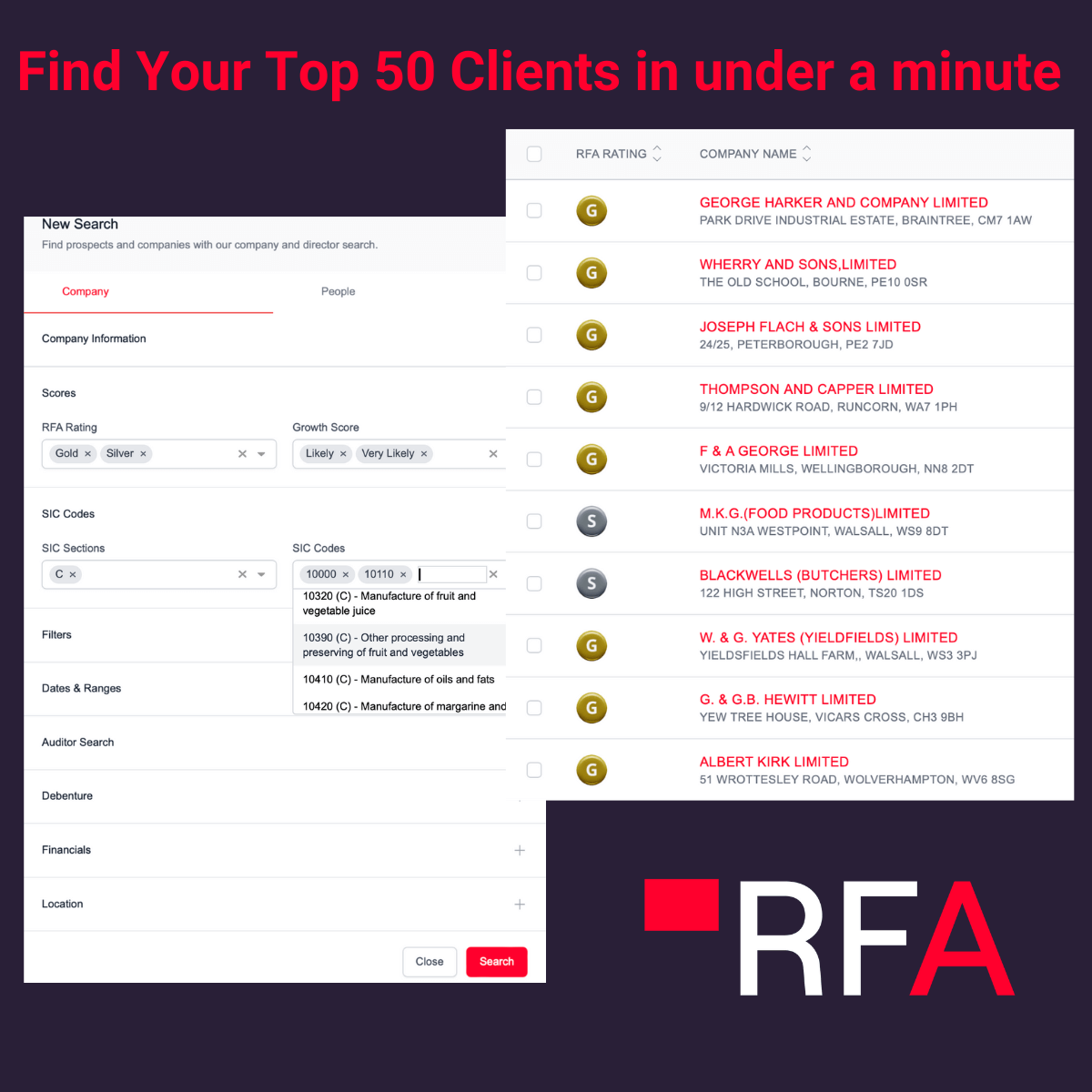

To learn how Red Flag Alert’s B2B prospector tool can help your business grow, get started with a free trial.